The Cradle of Forestry

Most people realize that North Carolina can boast of being “first in flight” and know well the story of the Wright Brothers launching their first airplane at Kitty Hawk, but fewer are aware that the State can also boast of being “first in forestry.”

The profession of forestry was first established in the United States in western North Carolina. This intriguing story begins when George Vanderbilt, a wealthy young man, first came to Asheville to bring his mother for medical treatment. Vanderbilt fell in love with the area and decided to build his home there – a 250-room mansion he later named Biltmore. He also began acquiring property, ultimately owning 125,000 acres. Much of the existing forests he acquired were in poor condition having been excessively logged, subjected to repeated wildfires, and cleared for substance farming and grazing.

Credit: By Biltmore Company – Biltmore Company, Public Domain

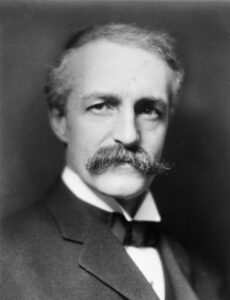

At the suggestion of his landscape architect, Frederic Law Olmstead, who was familiar with forestry as practiced in Europe, Vanderbilt hired the very first trained American forester in 1892. Gifford Pinchot, a wealthy young man from Pennsylvania, had studied forestry in France with the avowed purpose of launching the profession in America. During his time abroad he was genuinely concerned that someone else would achieve this goal before he could return from Europe. Arriving in February of that year, Pinchot wrote and implemented the first scientific forest management plan in the United States. Pinchot was to remain only three years and went on to become the first chief of the US Forest Service and later served two non-consecutive terms as governor of Pennsylvania. Along with five other foresters, he helped found the Society of American Foresters in Washington D.C. on November 30, 1900.

Credit: Pirie MacDonald – Library of Congress Online Collection

Upon Pinchot’s departure, Vanderbilt reached out to the leading forester in the world at that time – Dietrich Brandis – for a recommendation of a forester to replace Pinchot. Brandis suggested Dr. Carl A. Schenck, a German forester who held a Ph.D. from the University of Giessen. Schenck came to the U.S. and was immediately in way over his head. He knew little of US forestry needs, tree species, Appalachian culture, or democracy. He could speak English fluently, however, having learned the language to impress an English girl he had dated even memorizing Shakespeare’s “King Richard II.”

Schenck intensified the programs begun by Pinchot. He urged the construction of permanent forest roads to facilitate management activities, took steps to improve watersheds, and created a tree nursery. He undertook several projects to improve game and fish populations on Vanderbilt’s lands. As his reputation as a practical forester grew, Schenck was approached by several individuals seeking to become apprentices so that they might learn of this new concept called “forestry”. Recognizing the need for professionally trained foresters, he decided to open a forest school, and on September 1, 1898, on a site just a hundred yards or so from the present-day Cradle of Forestry in America Forest Discovery Center, the very first forestry school in the nation was established. Cornell University created the second school a few months later and Yale University, with a $150,000 endowment from the Pinchot family, opened the third school in the nation in 1900. But Schenck was first.

He was a demanding instructor and his 12-month curriculum was intense. Instruction took place in an abandoned schoolhouse until noon. After a quick lunch, students galloped along behind Schenck on horseback to complete various field exercises in the woods before dark. Classes included silviculture, surveying, forest protection, logging, tree and plant identification, forest mensuration, forest policy, and forest management to name a few. A total of twenty-seven courses had to be completed. A six-month internship followed the year of study and students had to submit a paper on their experience in order to receive a B.S. degree in forestry. Students received Sundays off and were given two weeks for Christmas; otherwise, they were fully engaged in learning. They either boarded with mountain families still residing on the property or occupied vacant cabins and cooked for themselves. Students gave these cabins picturesque names like “Hell Hole,” “Rest for the Wicked” or “Gnat Hollow” among others.

The combination of challenging teaching and splendid camaraderie produced an esprit de corps among the students which charged them with enthusiasm for their new occupation and sent them on successful careers throughout the world. When Schenck closed the doors of his school in October 1913, he could boast of the fact that he had trained 70% of all foresters then in America.

Robert Beanblossom retired after a 42-year career with the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources in 2015 and moved to North Carolina to become the volunteer caretaker at the Cradle of Forestry. He can be reached at [email protected]