They Sawed Up A Storm

In recognition of Women’s History Month, we are sharing a brief history of the nation’s first “women only” sawmill. A complete history of this mill can be found in Sarah Shea Smith’s 2010 book, They Sawed Up A Storm.

In 1938, a ferocious hurricane rolled up the Connecticut River Valley, leaving devastation in its wake. In addition to the damage to communities and homes, the storm left millions of board feet of timber downed. The US Forest Service initiated salvage efforts, often filling local ponds with logs for future sawing. One of the largest of these locations was Turkey Pond outside of Concord, NH, with roughly 12 million board feet of white pine.

By 1942, the United States was fully engaged in World War 2, and labor was short. There was an enormous need for supplies of all sorts, including lumber. New England white pine was often used to make boxes that carried supplies and ammunition from stateside factories to our troops and allies in Europe and the Pacific. With men of working age joining the military, the US Forest Service embarked on what was – at that time – considered a bold experiment: an “all-women” sawmill.

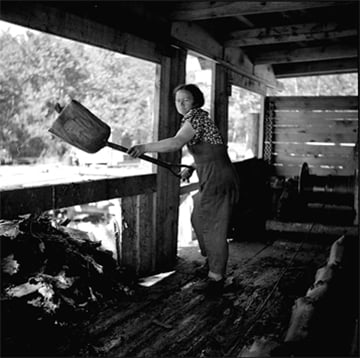

About a dozen women were hired – often from local farms – to conduct all the tasks at the mill, from rolling the logs out of the pond to stacking finished boards. The head saw was operated by a man, the husband of one of the mill workers – though he was often spelled by his wife.

Women, ranging in age from their teens to their 50s, were paid a starting wage of $4 per day to work at the mill, the same as a man’s wage in local sawmills. For comparison, a waitress at that time earned $1.40 per day, and a retail clerk $1.80 per day. Then as now, a job in the forest industry was a good job.

A 1942 article in the Concord Monitor notes that the mill was modified for the female workers: “The mill will have many safety devices never before considered necessary, for the protection of the women workers. It is also being rigged up with automatically operated saws and chain drives so that there will be no heavy lifting or pulling for the feminine crew.” Following the war, many of the changes made for the women-only sawmill quickly became standard practice in mills around New England, supporting improved safety and productivity (although a look at these pictures suggests that what is considered “acceptable footwear” in a mill has changed since 1942).

After roughly a year, the mill closed as the contract with the US Forest Service to saw salvaged timber ran out. Author Sarah Shea Smith notes, “It was intended to be an experiment. In the context of World War II, there was more interest and sort of social permission to do something like that. It was successful. It did what it was intended to do.”

Despite the closure of the Turkey Pond mill, women have steadily been playing a larger role in the forest products industry in the time since World War 2. It is paramount that we remember this important piece of history regarding the participation of women in the industry.