Young Forests Conserve Biological Diversity in the Lake States

Forests naturally exist in a continuum from nearly bare ground after a fire or other catastrophic event, to climax forests filled with trees that can reproduce in their own shade. Barring any disturbance, a stand in the former condition will progress through several stages to the latter condition. But there are, and always have been, disturbances. Wildfires reset the successional clock a little or a lot, depending on their intensity. Tornados, hurricanes, derechos, and other wind events can knock down individual trees, groups of trees, or entire forests. Insects and tree diseases can also set back succession. Therefore, it was never common for stands to stay in a given condition for long. Forests are always changing.

Humans have long been a part of this disturbance pattern. Ever since the dawn of human time, we have understood the power of fire to transform the landscape, often for the better. After a fire, it is easier to move through the landscape, easier to see game, the lush regrowth attracts game, and game can see predators coming from farther away. Early hunters likely started by hunting burned-over areas, but quickly turned to burning range to create better habitat, which is a well-documented practice by native Americans. But in this modern age, fire is no longer a friend. We do what we can to prevent stand-replacing fires over concern for human life and property.

Through the power of natural selection and the breadth of time, wild animals developed traits that helped them survive and thrive in specific habitats. The dominant species in one habitat will not even survive when placed in a different habitat. Driven by their needs to eat, avoid predation, and to procreate they have developed survival adaptations perfectly suited to their habitat. Every stage on the forest continuum has a suite of animals that evolved to its conditions.

One of the most difficult habitats to maintain is young forest habitat. Young forests are characterized by full light conditions, vegetative diversity, tree species and stem densities. Removing overstory trees allows full sunlight to reach the forest floor. Many trees, including aspen, oak, birch and jack pine need full sun and simply do not thrive in the shade. That light also allows understory plants to thrive, including raspberries, hazel, dogwood, and a host of forbs and grasses.

An entire suite of birds including American woodcock, golden-winged warbler, chestnut warblers, white-eyed vireo, American redstart and others nest on the ground or in low shrubs in this habitat. White-tailed deer, hares and rabbits, and bears feed on the abundant ground vegetation, nuts and berries. The high vegetative diversity of forest openings also produces an abundance of different insects. Wild turkey broods gorge on them all summer as their poults grow from 5 ounces to 12 pounds in their first summer. Even bird species adapted to mature forests bring their young to openings to feast on the profusion of insects.

As the young trees grow, they compete for resources and create a thick, dense young forest that offers prey species ideal escape cover. Young aspen is the preferred brood-rearing cover for the king of game birds – the ruffed grouse. Hunters understand grouse are still in dense young forests in early fall, where they are heard escaping but difficult to see – and even more difficult to shoot. Predators like broad-winged hawks have the same problem. Deer, moose and elk also love young forests, not only for the abundance of food. It is far easier to dodge a pack of wolves, or defend fawns and calves in a thick forest than in the open.

Because young forests grow and develop so rapidly, the dense young forest habitats required by so many wildlife species are available for only a short period of time, perhaps five to fifteen years. Therefore, young forests must continually be created to replace those habitats that are lost as other forests grow and become too open for many wildlife species. The continued establishment of young forest habitats using commercial forest management is essential to the long-term health of the region’s forest wildlife and to maintaining the diversity of life found in the forests of the eastern United States.

But maintaining young forest habitat is difficult in modern times. Creating the level of disturbance necessary to replicate the conditions of a stand-replacing fire, wind event or insect infestation requires intensive logging. Clearcutting has been deemed undesirable by some parties who don’t truly understand the need to use that tool to provide for trees that need full sun. Some land managers find it easier to use partial harvests or leave a lot of residual trees during logging to try to appease the public rather than educating them. Appeasement strategies are not helpful for the wildlife that need those habitats.

Many of the species in decline across the eastern United States need young forests. Golden-winged warblers are one of the most imperiled birds in the US, and rarely seen in their former Appalachian mountain strongholds. New England cottontail rabbit – a denizen of young eastern forests – are candidates for the Endangered Species List. American woodcock has declined by about 1% per year since 1968. And even the king – ruffed grouse – is in trouble. Once common across Indiana, hunting in the state was suspended in 2015 when it was listed as a Species of Special Concern. In fall 2019, it was added to the state endangered species list. And still, people oppose cutting trees there to create habitat for ruffed grouse and the suite of other animals that use the same young forests.

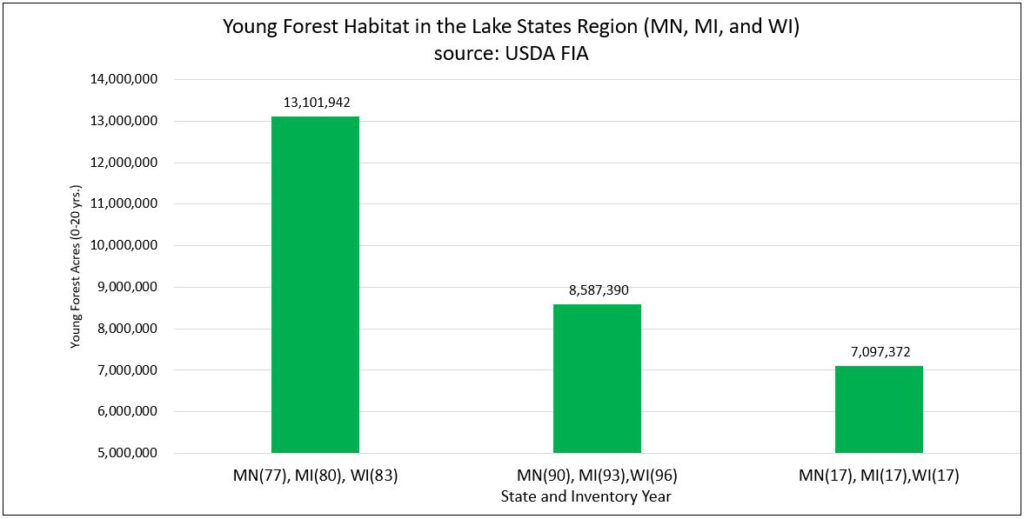

We are lucky here in the Lake States of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. We have a strong, vibrant forest products industry. We have an abundance of public lands managed by state, federal and county forestry programs. We have good public acceptance for logging and actively managing timber resources. We have safeguards in place through forest management guidelines, best management practices and certification standards that protect the region’s abundant waters, productive soils, cultural resources and biodiversity. And we have an educated workforce manning the increasingly complex harvesting equipment in a manner that ensures that what they are doing is sustainable.

It shows in our wildlife. About 95% of the global breeding population of golden-winged warblers is in the Lake States, where clearcutting aspen forests is still accepted and commonly practiced. Woodcock populations are faring better here than in the east. Every fall thousands of hunters flock to the region from all over the country for world-class ruffed grouse hunting. White-tailed deer are thriving and resilient to weather extremes and wolf predation.

Maximizing forest landscape diversity depends upon maintaining a mixture of forest types and, within those types, a variety of age classes. Each of these types and age classes is important to wildlife in its own way but does not necessarily host the same species. Many of the inhabitants of young forests do not utilize old forests, and vice versa. Because aspen is the only deciduous forest that is typically regenerated through clearcutting, the aspen forests of the Lake States region provide opportunities for sustaining young forest habitats and associated wildlife that are unavailable elsewhere in the East. By maintaining a broad spectrum of habitat conditions, we can accommodate a wide variety of forest wildlife and maximize our biodiversity in the region and beyond.