Volume, Value, and a Range of Markets for Forest Products

Over time, forest industries develop unique and inter-related ecosystems. These are where a range of markets support a complex and ever-evolving supply chain. While often competing, the reality is that mills depend upon one another to keep a unique balance of products that supports the entire supply chain, which in turn keeps wood coming to the mills.

Every area is unique in exactly how the relationships between a number of markets and the supply chain develops, but the principles are the same. Let’s look at Maine: On a percentage basis it is the most forested state in the country, with a range of forest types including spruce-fir, northern hardwoods and pine-oak. A robust and diverse industry has developed over centuries and now includes sawmills, pulp and paper mills, engineered wood manufacturers, biomass electric plants and others. There have been some big changes in the past few years (most notably the losses of pulp mills and associated biomass markets).

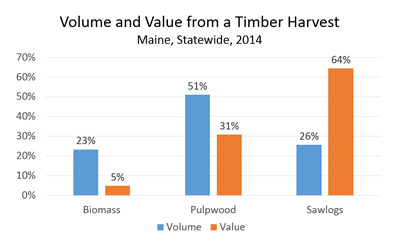

The Maine Forest Service publishes information on annual harvest levels by product, as well as average stumpage prices (the amount landowners are paid for their timber “on the stump”). Combined, these numbers allow analysis of how much different product types mean to the industry both for volume and value.

Maine forests produce saw log, pulpwood and biomass in addition to some specialty products as well, Saw logs that are sent to sawmills in Maine and elsewhere to be manufactured into lumber represent 26 percent of the volume harvested and 64 percent of the stumpage paid to landowners. This is where landowners make their money. Pulpwood is just over half of the harvested volume, and represents 31percent of the stumpage value. Biomass, sent to stand-alone electricity generation facilities or used for energy production at forest industries, were 23 percent of the harvest, but only 5 percent of the stumpage value.

The value figures discussed above are stumpage and represent the value to the landowner. But, that’s not the only way to measure value. Value to the logger and trucker is often simply volume-based (how much material was harvested or transported), and value to the region’s economy is impacted by how much is processed locally, how many employees are used in processing and specific innovations unique to the mill or region.

Since the beginning of 2014, Maine has lost markets for about 4 million tons of low-grade wood (pulpwood and biomass). A quick look at the value numbers above might suggest that it isn’t a huge problem because the money is in the saw logs. However, for those saw logs to get harvested, landowners also need markets for the other products. When low-grade material can’t move to a market, it is often the case that no material moves with landowners deferring harvests waiting for markets to develop.

Ideally over time, regions develop a variety of markets that provide a market for everything: the high value logs, the low-grade and markets for a full range of species and grades. There should be markets for mill residue and sawdust, and they can all work together to form a vibrant and interconnected forest products industry.

When markets close, this balance is disrupted. For example, when a pulp mill closes, it’s not only the workers at that mill that are impacted. The loggers that supply the mill are impacted as well as landowners in the region are left without options. Other markets in the region may have a harder time getting wood, particularly if some of the loggers leave the industry. These changes can be painful, but in the long-run may provide opportunities for new and innovative companies to establish operations.

Our industry relies upon a range of independent markets and the supply chain that is critical to their success. Developing and supporting a robust and dynamic supply chain allows those markets to sustain and grow.