Markets Are Important. That Becomes Obvious When We Lose Them.

Mills are critical to the forest products economy. Of course, we need the entire supply chain to grow, harvest, and process wood, but it’s the demand for wood by mills that makes the entire operation economically viable. That’s never clearer than when a mill (or in Maine’s case, mills) closes.

I recently had the opportunity to examine markets for low-grade wood in my home state of Maine using data from 2015 and 2023 (the last year with complete, public data). During this period, the state saw four paper mills close (Bucksport, Lincoln, Madison, and Jay), as well as three biomass power plants (Ashland, Fort Fairfield, Westbrook). These markets purchased a combined 4.4 million green tons of wood annually, or 400 truckloads of wood every day of the year.

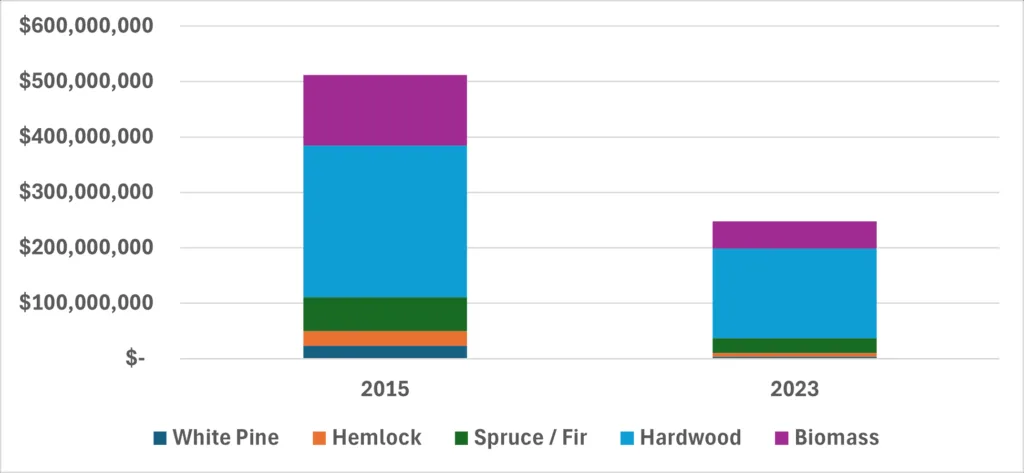

After losing these markets, statewide timber harvest fell from 13 million green tons in 2015 to about 8.6 million in 2023. Using the average delivered price ($ per green ton) for each year, the value of purchases of pulpwood and biomass from Maine timberland dropped from $512 million in 2015 (2023 dollars) to $248 million in 2023. This is the result of a significant loss of demand, coupled with a decrease in the inflation-adjusted per-ton price of every product (likely a result of reduced demand). This $264 million loss has been felt by Maine landowners, loggers, and truckers.

Milll-Delivered Value of Pulpwood and Biomass Harvested in Maine,

2023 Dollars

Having a full suite of markets for forest products is critical to effective forest management and enables full utilization of a timber harvest. Having outlets for sawlogs, pulpwood of a range of species, and a market for biomass allows landowners, land managers, and loggers to merchandise fiber to the highest and best use and to achieve the best financial returns for the entire supply chain.

With the loss of markets – both here in Maine and across the country – we often see products that simply don’t have an economically viable market (i.e., it would cost as much or more to harvest and truck the product than the mill will pay). I have visited logging jobs in two regions of Maine in the past year, where roundwood was being left in the woods because there simply wasn’t a place to sell it. This frustrated all parties, most visibly the logging contractors, who could not operate at peak efficiency due to limited opportunities for utilization.

Fortunately, as mills have closed, others have invested and expanded production capacity, and new market entrants have emerged. Entrepreneurs are looking for ways to utilize Maine’s 4.4 million tons of displaced demand. What’s critical to remember is that for companies to invest in new processing, they need to know that not only will the wood be there, but that the entire supply chain will be ready and able to adjust to meet future demand. Just as landowners, loggers, and foresters depend on mills, those mills equally rely upon a healthy and resilient supply chain.

Maine’s forest products industry employs nearly 12,000 individuals and contributes $8.3 billion to the state’s economy annually (2024).