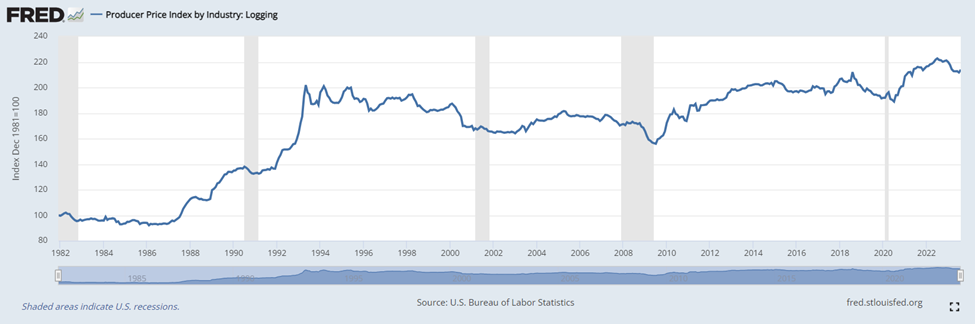

Producer Price Index for Logging

Across the country, I am hearing concerns about logging capacity – are there enough people and equipment to harvest the wood we need to support the industry of today and tomorrow?

One part of that concern is about what exists today, but a larger part, I believe, is about tomorrow – are enough people entering the logging profession, and how can they possibly afford to stand up a new crew?

Of course, there isn’t a universal answer to this question – the answer depends upon geography, local markets, and what is considered “enough wood” to feed markets. It’s clear that in the coming years, we’ll need more loggers, truckers, workers in the mill, and more of everyone.

One question I have heard a lot – from wood suppliers and consumers – over the last few years deals with inflation and its impact on logging. It is clear and not disputed that logging costs have risen – the cost of labor, diesel, parts, skidder tires, and just about everything else a logger buys have increased in the past several years. The questions end up being “How much?” and “Is this reflected in what loggers are being paid”?

That’s an interesting question, but not really how markets work. Yes, you can total up all of the input costs of logging (or any other economic activity), add a margin, and declare, “This should be the price.”

After that, prepare to engage in endless debate about whether the correct input costs were weighted correctly and discussions about why that might be the right cost structure for the entire nation, but it just doesn’t apply to (take your pick – geography, type of supplier, type of market, etc.). However, the market will ignore you – prices for commodities are set according to the dynamics of supply and demand, often somewhat disconnected from input costs.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes a monthly Producer Price Index for Logging if you want to follow what loggers are getting paid. What’s a Producer Price Index (PPI)? As the Department of Labor explains, a PPI “measures the average change over time in the selling prices received by domestic producers of goods and services. PPIs measure price change from the perspective of the seller.” In simpler terms, it is what a supplier gets paid for the goods they produce – in this case, logs, pulpwood, biomass, and other forest products. Notably, the PPI is without value judgment – this isn’t what someone “should” get paid. It’s what they did get paid.

The PPI for Logging sets January 1981 as the base date, with a value of 100. As loggers’ paid wages rise and fall, a monthly report puts this in perspective to 1981. As you’ll see in the chart below, by May 1993, the Logging PPI had risen to a little over 200 – meaning that loggers were getting paid double what they were paid in January 1981 (note – the figures are not adjusted for inflation).

A look at the most recent years (2020 through today) shows a rise in what loggers are paid from mid-2020 through late 2022, with some declines from there to the present. According to this PPI, loggers were getting paid 11% more in August 2023 than at the start of the decade but 4% less than at the PPI peak in July 2022.

The PPI can be a valuable tool for loggers, wood-using industries, and others who care about the long-term health and viability of the forest products sector. It helps understand – at a macro, national scale – what loggers are getting paid, and can be considered in context with other information to ask, “Are loggers being paid enough to economically incentivize them to stay in the business, invest in the future, and be sustainable parts of the supply chain?” Of course, there aren’t easy or universal answers to this question, but it is critical to ponder. The PPI for loggers is one data point to help inform the answer.