The Fisher Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances | A Proactive Approach to Recovery

Landowners and managers have choices and responsibilities when it comes to threatened and endangered species conservation. Successful long-term forest management and conservation are possible when ‘win-win’ solutions are created that advance the integration of forestry and wildlife. Many tools are available to help achieve this objective including a suite of proactive management plans under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). These plans encourage land management activities that benefit wildlife and business by enabling the development of site-specific strategies that are tailored to management objectives, values and the needs of wildlife.

The conservation plans are voluntary agreements between the landowner and government agency (or several agencies) that benefit wildlife and also create long-term regulatory stability. They aim for a net conservation benefit which means that habitat conditions will become better than they currently are, over the life of the plan. Enrolling in one provides an incentive to manage the land in ways that increase wildlife habitat and that may attract listed species or increase their populations and distribution. They provide federal assurances in the case that management activities lead to incidental ‘take’ of a federally listed species. The plans describe anticipated effects of proposed activities and include conservation measures that address those effects. One such plan is the Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA).

A CCAA is an agreement whereby non-federal landowners agree to help promote the conservation of a candidate species that occurs on or has the potential to occur on the ownership and may later become listed under the ESA. In return, landowners receive assurances against additional land-use restrictions should the species covered by the CCAA ever become listed for protection under federal law. Conservation measures outlined in the CCAA are designed to support recovery efforts. The states of Washington and Oregon have developed fisher CCAA’s in collaboration with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), state agencies, and private and tribal landowners to facilitate reintroduction and recovery efforts and provide regulatory certainty.

The fisher (Pekania pennanti) is a small, carnivorous mammal native to the coniferous and mixed forests of Canada and the northern United States. They are solitary forest-dwelling predators that are rarely seen. They prey on small to medium-sized mammals and birds and are one of the few specialized predators of porcupines. They are hunters but will also scavenge or eat insects, nuts or berries when prey is not available.

Fisher seeking cover on the forest floor. Photo by John Hader

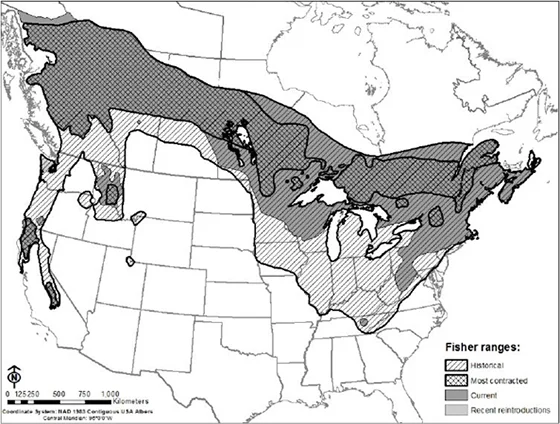

During the 19th and early 20th centuries the fisher declined over much of its range because of excessive fur trapping, predator/pest control and alteration of forested habitats. The high value of the skins, the ease of trapping, and the lack of regulations resulted in over-trapping and is believed to have been the primary initial cause of fisher population losses. Conservation and protection measures to reduce trapping and re-introduce fisher back into their historic range have allowed them to rebound and continued efforts will facilitate recovery success.

Historical and current Fisher distribution in North America (2014).

Fishers inhabit upland and lowland forests, including dense coniferous, mixed, and deciduous forests, as well as early successional forest with dense overhead cover. They are associated with mature, structurally diverse forest habitats that have abundant snags, understory, and coarse woody debris. They will den in tree-top cavities located in snags or live trees which provide protection against the elements and potential predators. They also utilize the forest floor woody debris for denning, resting, and foraging and use ground cover for protection when they are on the move. As such, fisher generally avoid open areas and areas with limited forest cover.

Fisher inhabit coniferous, deciduous and mixed forests that are structurally diverse.

Timber harvest can fragment fisher habitat, reduce it in size, or render the forest structure unsuitable. The fisher is opportunistic and although habitat loss is named as one of the reasons for its decline, it is not thought to be the limiting factor. With availability of prey, and suitable resting/denning habitat, it is believed that fisher will be successful in a variety of forested habitat types.

Attempts to list the west coast population of the fisher under the ESA began in 2000. It is believed that the proactive efforts of many partners has been and continues to be a major factor in staving off listing.

Conservation Timeline for Fisher Recovery

2000 – The west coast population of the fisher was petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA)

2004 – A status review found that the listing was warranted, the fisher was added to the waitlist of eligible candidate species

2008 – Sierra Pacific Industries entered into a ground breaking CCAA

2014 – The west coast population of the fisher was proposed for listing as threatened under ESA

2016 – The ESA listing was determined as unwarranted and the proposal was withdrawn

2016 – The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife enter into a CCAA and invite landowners to enroll

2016 – The withdrawal was legally challenged

2017 – The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service proposes a CCAA for western Oregon and invites landowners to enroll

2018 – First hearing scheduled regarding the legal challenge

The fisher CCAA’s allow landowners to improve habitat without incurring additional restrictions if the size of the area occupied by the fisher increases or the population increases or if it becomes listed in the future. There is an overall net conservation benefit and it is expected that such conservation efforts will prevent the need to list the fisher in the future.

In its recent decision to not list the west coast population of the fisher under the ESA, USFWS specifically mentioned landowner enrollment in CCAA’s as an example of ongoing conservation efforts that contributed to the decision, but there is no guarantee the agency will not do so in the future. It is possible that federal regulators may propose a new listing if recovery efforts do not meet expectations or as a result of the lawsuit that was filed challenging the decision to withdraw the listing. For that reason, enrolling in the program not only allows landowners to obtain land-use assurances, but also supports fisher recovery and ensures that a federal listing is not needed in the future. Landowners can continue to enroll so long as fishers in Washington or Oregon state are not listed for protection under the ESA. While wildlife managers expect that most fishers will remain on the national parks and national forests where they are released, they want to provide protection for any that move onto non-federal lands.

As part of the proposed CCAA’s, landowners agree to conservation measures such as: work with wildlife managers to monitor fishers and their dens in the event that a den site is found, avoid harming or disturbing fishers and their young associated with active denning sites (March to September), and report den sites and sick, injured, or dead fishers.

Re-introducing fisher throughout their historic ranges is thought to be the main tool to promote successful recovery. Re-introductions have been underway in Washington, Oregon and California. The re-introduced fishers are equipped with satellite transmitter collars, they are being tracked to determine habitat selection, distribution and success of denning. The goal is to establish fishers into recovery areas and the effort will be considered a success when self-sustaining populations are established across those zones.

Fisher equipped with satellite transmitter collar. Photo by J. Mark Higley